From Birtwistle to Stormzy: why tradition must always be challenged

Keith Burstein

Monday, April 22, 2024

Composer Keith Burstein explores how music has changed in the three decades since The Hecklers booed Sir Harrison Birtwistle at the Royal Opera House – and reflects on why he felt called to such radical action in the first place

It is 30 years since The Hecklers caused a riot at the Royal Opera House on 14 April 1994. What has changed in music since then? From Spectralism to Radical Romanticism, from Errollyn Wallen to Stormzy, the music of today is kicking and alive. Traditionalism has been renewed by innovation.

Thirty years ago, things didn’t look so promising.

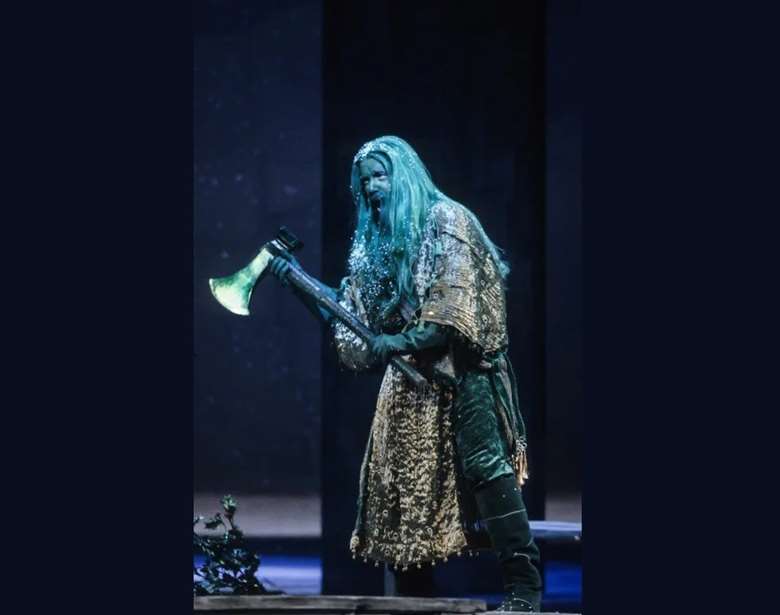

Back in 1994, a small group of composers – dubbed The Hecklers, of which I was a co-leader – went to London’s Royal Opera House to boo an opera by atonal composer Sir Harrison Birtwistle (having announced our intention to do so in advance to the press). The problem was not that the music was too modern for us – just the reverse – it was that it was too old-fashioned. Atonalism was, even in 1994, almost 100 years old.

All hell broke loose. The atmosphere was something like that after a coup d’etat – as though the unsayable had been said, in short that the Emperor of Atonalism was naked, and as in the classic myth; once pointed out, everyone could see.

"Music exists to serve the profound family of humanity – not a clique or a cabal"

In part the problem – and the extraordinary scandal that erupted – can be attributed to the fact that a kind of apparat of functionaries had developed over decades around the atonal culture due to the heavy aspect of subsidy through public money. Of course, the Arts need and deserve support and where necessary this should come in part from public sources, but in the case of atonalism all connection with the public had been lost – or never found. The music-loving public has never loved atonalism, or indeed even noticed it, even after a century of force-feeding it to them.

Now, 30 years later what has changed? The answer is nothing and everything.

Nothing, in the sense that the atonal paradigm bandwagon still rolls, but with very wonky wheels, one of which has dropped off and the other three are about to go. Until it actually does stop rolling, nothing can really change in the field of new classical music. It is still ‘verboten’ to write in romantic tonal melody and harmony. This idiom cannot be allowed as art music to this day.

Yet, The Hecklers did let the genie out of the bottle and now out it cannot be put back in. At the very least what was released that night was a new openness to pluralism in the field of new classical music. All that had to happen for the evident fact that all music is tonal to quietly reassert itself, was that composers began to allow the pretence that their music was not tonal to be dropped. And, if all music is tonal (because tonality is an aspect of the very structure of sound and the Harmonic Series – a non-human phenomenon of nature), then to allow tonality to sound again is merely to partake of an infinite resource of human expressivity.

"The Hecklers did let the genie out of the bottle and now out it cannot be put back in"

This has nothing to do with being against experiment. Indeed, all traditions need to be renewed or else they die. The move to question the atonal status quo is, paradoxically, what allows the process of experiment to resume. Atonalism was fossilised and this fossil had a strangle hold on the whole new classical culture. Now we see the natural flow of experimentalism moving back into tonal melody and harmony which is the inexhaustible rock bed of music everywhere.

What is happening around us? On the one hand, there is my idiom of Radical Romanticism. But my evocation of the spirit of romanticism charged with contemporary sensibility is only one way. Others take inspiration from the frequency-based ‘Spectral’ composition that began in the 1970s with the likes of Gérard Grisey. One modern-day example of that is my friend James Helgeson, a great lover of the atonalist, modernist tradition who would not have been a Heckler, now or then. Helgeson’s most recent work, which I heard only a few days ago is a piano trio that deploys this shimmering phantasmal world of glittering, fleeting webs of sound related to the underlying structure of sound itself, the Harmonic Series. While relatable to the atonal idiom, this half-child of atonalism and tonality also suggests a move back towards the thematic with a long passage evoking an unheard Bach quotation through a composed countermelody played in ethereal high harmonics.

Then there is Errollyn Wallen, born in Belize and brought up in Tottenham, who has stormed the world in recent years, writing music for the opening of the London Olympics, re-writing Jerusalem for the Last Night of the Proms and now the most prolific composer in the country. Most recently, I went to a recital of Errollyn at the Wigmore Hall, where she sat at the piano and sang into a microphone. The very image of the singer-songwriter in an idiom that was at once jazz, improv and classical all fused into one.

"the Emperor of Atonalism was naked, and as in the classic myth; once pointed out, everyone could see"

And what of other genres of music, Rap for instance? Now as at home in the arts pages as Schubert or Beethoven. In Stormzy we have one of the great socio-artistic forces of our time, processing as Mozart and Verdi did before him the societal dynamics that burn and create our community anew. His eloquence, pathos and power are a thing of beauty.

And while the century-long dominance of the atonal paradigm is over and the small but culturally powerful domain of so-called ‘new classical music’ may be finally escaping its deadly grip, other streams of music have remained unabashed in their radiantly romantic tonalism. Think of recent geniuses, Amy Winehouse, Eminem, or Björk, whose unique, epically voiced passion still reverberates on from her Icelandic Fiefdom. More Nordic wonder came from Kalevi Aho’s Theremin concerto at last year's Proms, a mighty mass of magical sound with spine tingling grandeur.

And now we have movement at the very heart of the beast; BBC Radio 3, which for so many decades almost single-handedly sustained the atonal desert. Sam Jackson’s appointed as head of the channel is a radical move. Formerly of Classic FM, Jackson promises a real shake up – and shake down. A howl of protest has gone up from the ivory tower of privilege as they see their formats and cosy club having a makeover. It isn’t, and should never have been, a private enclave at public expense. Music exists to serve the profound family of humanity – not a clique or a cabal.

In short, things are looking up compared to 30 years ago when I, a shy and retiring classical musician, was tempted to lead a direct action protest. I don’t kid myself the improvements are all down to that night, but we did bring a spotlight to bear upon the question and all we wanted to do was open up a debate.

Now our world is awash with ways of evoking from the infinite ocean of tonality – what I call SuperTonality – the new types of feeling, thinking and hearing which will create our 21st century musical landscape.