Dr Graham Griffiths on the life of Leokadiya Kashperova

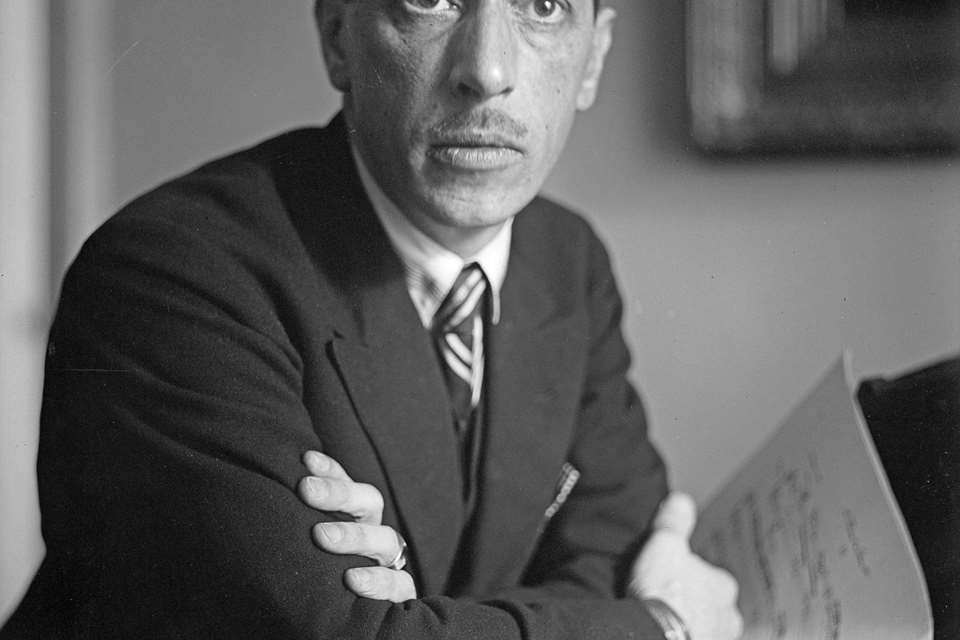

Dr Graham Griffiths

Thursday, December 8, 2022

Dr Graham Griffiths will join Donald Macleod in the studio next week to discuss BBC Radio 3 composer of the week, Leokadiya Kashperova. Having spent 20 years researching and writing about Kashperova as concert pianist, piano teacher and, more recently, as composer, Dr Griffiths offers us some context on this recently rediscovered Romantic composer.

Register now to continue reading

Don’t miss out on our dedicated coverage of the classical music world. Register today to enjoy the following benefits:

- Unlimited access to news pages

- Free weekly email newsletter

- Free access to two subscriber-only articles per month