Artist Managers: Norman Lebrecht on artist management's changed landscape

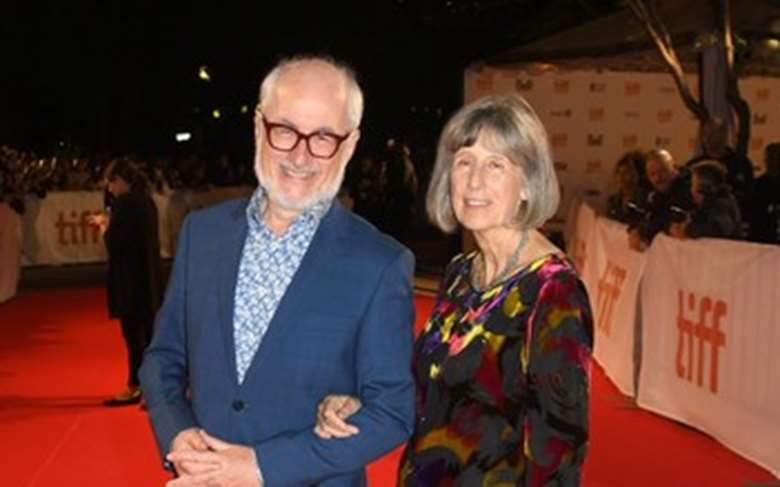

Andrew Green

Wednesday, December 1, 2021

On the 25th anniversary of Lebrecht’s book, Who Killed Classical Music?: Maestros, Managers, and Corporate Politics, Andrew Green sits down with the founder of Slipped Disc

Register now to continue reading

Don’t miss out on our dedicated coverage of the classical music world. Register today to enjoy the following benefits:

- Unlimited access to news pages

- Free weekly email newsletter

- Free access to two subscriber-only articles per month