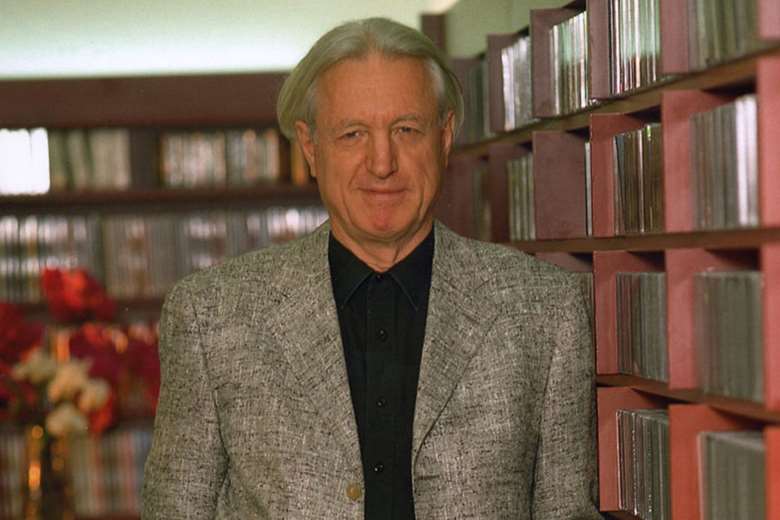

Naxos founder Klaus Heymann on the label's history - and what comes next

Simon Mundy

Wednesday, July 21, 2021

'Actually, the rudeness did us a big favour. None of the record shops would put us in their ordinary racks so we started putting in our own display stands'

Register now to continue reading

Don’t miss out on our dedicated coverage of the classical music world. Register today to enjoy the following benefits:

- Unlimited access to news pages

- Free weekly email newsletter

- Free access to two subscriber-only articles per month